| The Very Highest Quality Information... |

| French Coins |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ancient French History

The area encompassing most of modern France was known to the Romans as Gaul, which was populated by various independent tribes sharing a similar Celtic language and culture. Between 58 and 51 BC, the legendary Roman Julius Caesar conquered most of Gaul and incorporated it into the Roman Empire, winning glory for himself and paving the way for his rise to total power.

Gaul subsequently became heavily romanised, and it is believed that native Gallic culture effectively disappeared after a few centuries under Roman rule. As the Roman Empire declined in the west during the 3rd to 5th Centuries, Gaul was subjected to repeated invasions and raids by the Franks, a Germanic confederation of tribes, whose name is the etymological ancestor of the word 'France'. By the end of the 5th Century, the Franks had overrun all of Gaul and established their own kingdom under the Merovingian Dynasty.

Frankish Kingdom

The Franks were initially pagans for the most part; worshipping Germanic gods similar to those worshipped by the Vikings and Anglo-Saxons, but had largely converted to Christianity by the end of the 7th Century. The Merovingian Dynasty came to an end in 751 AD when the pope deposed Childeric III in favour of Pepin the Short, son of Charles Martel, the victor of the Battle of Tours. The crowning of Pepin the Short marked the beginning of the Carolingian Dynasty.

Charlemagne

Pepin the Short's son, Charlemagne succeeded him in 768, along with Charlemagne's brother Carloman I, who died in 771. Under Charlemagne, the Carolingians expanded the Frankish kingdom to include Bavaria, Carinthia, Saxony, Lombardy (including Rome) and the Spanish Pyrenees. As well as being King of the Franks, Charlemagne was the founder of the Holy Roman Empire, having been crowned as 'Emperor of the Romans' in 800 AD by Pope Leo III. During the course of his lifetime, Charlemagne had at least 20 children, and many genealogists believe that all living humans of European descent are ultimately descended from Charlemagne himself.

France

The Kingdom of France can trace its origins to the breakup of the Carolingian Empire in the early 9th Century following the death of Louis the Pious in 840. The death of Louis triggered a power struggle amongst his sons, which led to the division of the Empire between the brothers, with the youngest, Charles the Bald, taking West Francia, Lothair the nominal title of Emperor of the Romans along with Middle Francia, and Louis the German Eastern Frankia. Eastern Francia eventually evolved into the Holy Roman Empire, whilst Western Francia would eventually evolve into the Kingdom of France. Middle Francia would dissolve into a variety of smaller states that would be squabbled over for centuries by the Germans, French and Italians.

France during the Middle Ages

The Carolingian Dynasty came to an end with the death of Louis V in 987. Having left no legitimate heirs, an electoral assembly at Senlis voted to give the Crown of Francia to Hugh Capet, Duke of the Franks and Count of Paris. The Capetian Dynasty, and its cadet branches, the Valois and the Bourbons, was to rule France for the next 800 years.

In the 11th Century, Pope Urban II, a Frenchman, initiated the 1st crusade to the Holy Lands to recover them for Christianity. Urban II was partly motivated by the bloodshed he saw in his native land caused by the internecine strife between the squabbling French nobles, trying to channel their aggressive warrior spirit to fight the Saracen enemies of the Cross instead of their fellow Christians. France was one of the key supporters and contributors towards the centuries-long and ultimately doomed attempt to install and maintain a permanent Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Holy Land.

Although France was a large, populous and prosperous nation, it was very decentralised during the Middle Ages, and the Kings of France held only nominal authority over the lands outside the Ile de France that they owned directly as the Counts of Paris. The result of this is that the French Kings often found themselves contending with over mighty subjects who were his nominal vassals, including the Dukes of Aquitaine and Normandy and Counts of Ponthieu, who also happened at various times to be the Kings of England. In 1337, one of these Kings, Edward III of England, laid claim to the throne of France itself on the grounds that he was a descendent of Philip IV via his mother, Isabella of France, a claim that had some legitimacy under the English succession rules of male-preference primogeniture but not under the exclusively male laws of succession under French Salic Law.

This claim would be the start of the 100 years’ war between England and France, lasting until the 1453, although the claim was not technically abandoned by English/British Monarchs until 1800. The Hundred Years War was fought mostly in France, and France suffered most of the devastation, which also coincided with the arrival of the Black Death. France nearly suffered the unimaginable horror of having an English king sitting upon her throne following the Victory of England's Henry V over Charles VI of France following a series of campaigns in the 1410s. France was only spared this indignity when Henry V died of dysentery in 1422, leaving an infant Henry VI presiding over a fractured and divided Kingdom at home as Charles VI's competent son and heir Charles VII, previously the disinherited Daphin of France, resumed the French campaign against the English, aided in part by an illiterate teenage peasant girl called Joan claiming to hear the voice of God in her head, who helped to inspire the similarly uneducated and religiously credulous French armies to victory after victory.

However, it wasn't until 1453, some 22 years after the brutal execution by burning of Joan of Arc, that the last battle of 100 years’ war was fought, at Castillon. After this, the English were driven out of France everywhere except for Calais, which also fell to France just over 100 years later in 1558.

The Bourbon Dynasty

During the 16th Century, the ideas of Martin Luther were sweeping through Europe, including France. The largest of these protestant groups were the Calvinist Huguenots. Tensions between the Huguenot reformers and Catholics increased, and in the 1560s degenerated into open warfare. It was into this atmosphere that Henry, King of Navarre succeeded to the throne as Henry IV of France, the first Bourbon King in 1589.

Henry IV was a Huguenot, but found that his claim was strongly resisted by the majority of French Catholics, particularly in Paris. In 1593, he abandoned his Calvinist faith and converted to Catholicism in a pragmatic attempt to secure his throne. He did however, as a favour to his former co-religionists, issue the Edict of Nantes in 1598, prescribing the toleration of Protestants. This liberal and tolerant attitude was not universally accepted however, and Henry IV fell victim to assassination by a Catholic Fanatic in 1610.

Rise of Absolutism

Against the backdrop of religious conflict that was still taking place into the 17th Century, the French Crown, led largely during Louis XIII's reign by Cardinal Richelieu. The French Crown eventually broke the power of the French Nobles by issuing an edict in 1626 demolishing internal castles on the grounds that they were not needed to defend from foreign invasion, reducing the capability of the local landowners and Huguenots to rebel. The Estates-General, a kind of French Parliament (although one which only had a consultative role) was convened in 1614, and was not convened again until 1789. Charles XIII's successor, Louis XIV, further consolidated his authority by requiring the French nobility to spend part of the year in Versailles in order to keep an eye on them and prevent them from plotting against him. Most of the nobility did not seem to appreciate the true motivations behind this policy, or at least did not care, as they viewed this requirement as a privilege, rather than a humiliation.

The Sun King

Louis XIV was one of the longest reigning monarchs in European History, reigning for over 72 years, from 1643 to 1715. The first few years of Louis XIV's reign were dominated by Cardinal Mazarin, Richelieu's chosen successor as chief minister. The French Crown faced the challenge early on from sections of the French nobility who opposed the encroachments of the French Crown on their traditional rights. Perhaps partly inspired by events across the Channel in England, began a series of rebellions against the Crown starting in 1648. A large part of the Conde cause was over the feudal rights of the nobility, and so was not therefore a cause that enjoyed universal support amongst the French population. The chaos and disorder that the Fronde rebellions brought discredited the Crown's opponents and people perceived that rule by the Crown would bring much needed law and order to the country. Louis XIV fought a series of wars against the Bourbon's most hated enemy, the Habspurgs, and ultimately succeeded in replacing the Spanish Habspurg dynasty with his grandson Philip and his descendents. When he died in 1715, the French Crown was stronger than ever.

The Monarchy Weakens

Louis XIV's eldest son and grandson predeceased him, and so he was succeeded by his great grandson, Louis XV, who went on to be another of France's longest lived monarchs. Although the machinery of monarchical absolutism had been put in place by his two predecessors, he was not the man his great-grandfather had been. He took little interest in the affairs of state, leaving the administration of government largely to his ministers, who governed in his name. He did however take an interest in matters of war and foreign policy, and France successfully prosecuted the War of Austrian Succession against the Habspurgs between 1740-1748. He lost the popularity he had gained however, when he agreed to return the Austrian Netherlands to Austria, a decision which mystified most French people.

The 7 Years War of 1754-1763 against Britain and its allies went very badly for the French however, and the French Crown got into considerable debt. This debt worsened under Louis XVI, Louis XV's successor, when France entered the American War of Independence on the side of the colonists. Although France was on the winning side of the conflict, France's debts were exacerbated. By 1789, the French Crown was desperate for new revenue, but was under political pressure to consult the Estates-General in order to legitimise a new tax regime. And so, for the first time since 1614, a new Estates-General was convened.

Revolution

The Estates General consisted of 3 Estates, Clergy, Nobility and Commoners. The Third Estate of Commoners demanded reforms to government, including a written constitution that would set out and limit the powers of government, particularly those of the monarchy. Louis XVI attempted to prevent the Third Estate, now calling itself 'The National Assembly' from using the Salle Etats to meet. The members of the 'National Assembly' decided to convene in a nearby tennis court instead, and pledged an oath not to dissolve until a constitution had been agreed. A rumour that the Royal Government had sent soldiers to forcibly dissolve the assembly inspired a rebellion by mobs in Paris, who stormed the notorious prison fortress, the Bastille, seized its arsenal and murdered the governor.

After 3 years of political manoeuvring, and a failed attempt to flee Paris, Louis XVI was deposed as King and beheaded the following year, the Monarchy was abolished and a Republic declared. Over the next few years, revolutionary terror imposed by various political factions, as well as attempts by foreign monarchs to invade France and re-install the Bourbon monarchy, led to great bloodshed in France.

Napoleon

Out of the chaos and anarchy of the revolution rose Napoleon Bonaparte. Previously an obscure ethnic Italian artillery officer from Corsica, Napoleon engaged in political machinations that saw him rise to power first as consul in a triumvirate, to first consul and finally Emperor of France. Napoleon lacked any hereditary legitimacy, and realised that martial glory would be a good way of securing his hold over France. Napoleon was a highly skilled general, and his military genius almost secured French hegemony over the whole of Europe. In addition to his military prowess, his legal reforms and the spreading of the revolutionary metric system had a profound effect over the hearts and minds of people in Europe, and had a lasting political influence in France and the rest of Europe, despite his ultimate defeat and exile at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Continued Revolutionary Instability

Following the Defeat of Napoleon, the Bourbon Monarchy was restored. Louis XVI's brother was restored to the throne as Louis XVIII (Louis XVI's son, the dauphin was considered by monarchists to have reigned as XVII after his father's execution until his own death in captivity in 1795). Louis XVIII was an absolutist by inclination but was wise enough not to antagonise the French population too much by pushing this too hard. His own successor, Charles X was not perceived as a hard-core reactionary and his attempts to reinstall the powers of the Catholic clergy, disband the National Guard (but not disarm them) and suspend the constitution finally led to his overthrow and replacement as King by Louis Philippe, a member of the Bourbon Cadet Branch of Orleans.

Although Louis Philippe was initially popular as a constitutional monarch, republican sentiment remained strong in France, and he too was forced to abdicate and flee when revolution swept through France and the rest of Europe in the wake of rising food prices and a ham-fisted attempt at political repression in response to the rising discontent.

The downfall of the Orleanist Monarchy led to the creation of Second Republic. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon's nephew, was elected as president of the new Republic. Following a coup 4 years later, he had himself declared emperor in 1852 and attempted to emulate the military glory of his uncle, he engaged in building an overseas Empire, in competition with the British. In wars against major powers, he was not quite as successful. Although he participated on the winning side of the Crimean War against Russia in the 1850s, he was eventually deposed as emperor during the Franco-Prussian war following his defeat and capture at the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

Following the defeat of France (which also resulted in the loss of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine) an uprising in Paris led to the city coming under the control of the communards, a broadly socialist, communist and anarchist movement who created the Paris Commune, who ruled Paris from March to May 1871, when they were crushed by French Government troops at the urging of the victorious Prussians. The Third Republic had by now come to power, and some measure of political stability had returned to France.

Franco-German Relations and World War I

The loss of the Franco-Prussian War and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine was a cause of bitterness between France and Imperial Germany, and for many years France longed for revenge. As the result of rising tensions, most of the major powers of Europe divided into two camps, eventually settling into the Triple Entente between France, Russia and Britain (the latter of whom feared the rise of Germany as a naval and industrial power) Germany for its part, entered into an alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy (the latter of whom abandoned the alliance before the outbreak of war).

As the result of a chain of events stemming from the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz-Ferdinand by a Bosnian-Serb nationalist, Russia mobilised its army and prepared for war. Germany declared war on France and following a plan developed years before, invaded France via Belgium in an attempt to knock her out of the war before Russia could fully mobilise its colossal army (known to many German strategists as 'the Russian Steamroller') The violation of Belgian neutrality brought Britain into the war. Germany advanced rapidly, but failed to capture Paris and was driven back. What followed was 4 years of bloody trench warfare, resulting in huge loss of life, particularly for the French, who suffered the loss of nearly 1,700,000 killed, a disproportionate amount of whom were, for obvious reasons, young men. France proportionately more deaths than any other allied nation, with the death toll constituting over 4% of its entire population.

World War II and Nazi Occupation

The harsh peace treaty imposed on Germany after the war meant that it was Germany's turn to feel bitterness for losing a war. The rise of the Nazis in Germany led to a massive re-armament program in Germany and the re-emergence of German bellicosity. With memories of the slaughter in the trenches still fresh in the minds of France and its British ally, the French pursued a policy of appeasement throughout most of the 1930s, hoping to avoid another war with Germany. The invasion of Poland proved a step too far however, and Britain and France both declared war in September 1939. The next few months were relatively quiet in France, but in May 1940, a sudden Blitzkrieg rapidly defeated allied forces on the continent, and France was occupied by the Nazis until 1944. A puppet government was set up in Vichy, in the South of France, headed by Marshal Petain, the hero of Verdun. Vichy France also administered most of France's overseas Empire, and remained officially neutral for most of the war, although the Free French, led by de Gaulle and supported by the allies, launched a series of campaigns to bring as much of the French Empire under his control as possible.

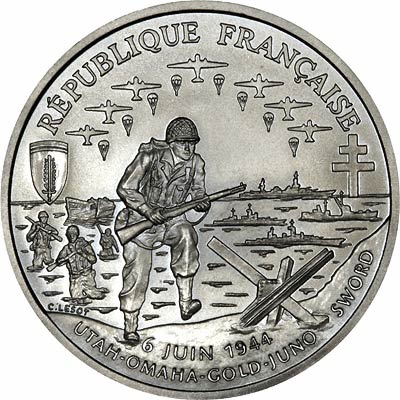

Following the D-Day landings, France was liberated.

Post War

France took some time to recover from the war, and underwent an economic crisis which forced a devaluation of the Franc in the late 1940s. France attempted to hold onto her Empire by fighting a series of wars against independence movements in Algeria (1954-1962) and Vietnam (1950-54). They were ultimately unsuccessful. Meanwhile, France also supported moves to forge closer ties with other European nations in order to prevent the possibility of further wars. She entered the Coal and Steel Community in 1952 with Germany Italy and the Benelux nations. From this body emerged the EEC and the EU, of which France is a leading nation.

Coinage of France

Roman coins were used in France even before the conquest of Gaul be Caesar. Several Roman mints were established in Gaul, the most important of which were located at various times Arlentum (modern day Arles). Charlemagne introduced silver denier in the late 8th Century AD, along with the accounting system of £sd, upon which the old English system was based. The old French currency was similarly divided into 20 denier (pence) to the sou, and 20 sou (shillings) to the livre (pound).

This predecimal system lasted in various forms until 1795, when the French franc was introduced, divided into 100 centimes. The franc itself was named after a coin minted between 1340 and 1641, first in gold and then in silver, which was worth 1 livre tournois.

Despite this, the Franc was worth slightly less than the old livre, and was valued at the equivalent of £1/-3d French. By this time, the French currency had been debased considerably compared to its English/British equivalent, and the French franc was a silver coin containing 4.5g of fine silver.

The franc coin was supplemented by copper 1 and 5 centimes (the latter of which was known as 'the sou' after the old pre-decimal coin). The 5 franc silver coin came to become known colloquially as 'the ecu' after another old French coin of similar value.

In 1803, Premier First Consul Napoleon introduced a gold 20f coin, which henceforth came to become known as 'the Napoleon' gold issues in 5, 10 and 40 francs were also issued. Under the reign of Napoleon III, Gold coins of 50F were introduced. Following the 1848 revolution, copper was replaced with bronze for the lower denominations up to 2 decimes (20 centimes).

The 20F coin of 0.1867 troy ounces of gold (struck in 0.900 fine) was the basis of the Latin monetary unit used in other Latin monetary union states between 1865 and 1927 (although the Latin monetary union effectively came to an end during the First World War). The trauma of the First and Second World Wars, as well as the interceding Great Depression had a devastating effect on the French Franc, by 1960, when it was replaced by the new franc at 100-1; it was worth only a tiny fraction of its value 45 years before. The old 1 Franc coins continued to circulate as 1 centime coins for some years afterwards.

By the time the French franc was withdrawn from circulation in 2002 (to be replaced by the euro) coins of 5, 10, 20 centimes and ½f, 1f, 2f, 5f, 10f, 20f were typically used in circulation.

For Sale and Wanted

If you are interested in coins from France please see our product index:-

French Coins

Gold Coins

We also have gold coins from France on our taxfreegold website:-

French Gold Coins

| ...at the Lowest Possible Price |

|

32 - 36 Harrowside, Blackpool, Lancashire, FY4 1RJ, England.

Telephone (44) - (0) 1253 - 343081 ; Fax 408058; E-mail: info@chards.co.uk The URL for our main page is: https://24carat.co.uk |

Web Design by Snoop |