| The Very Highest Quality Roman Coins |

| Ancient Roman Coins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

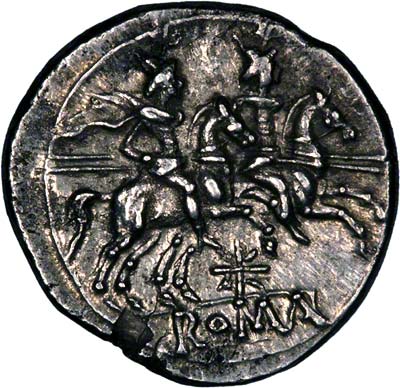

Before the use of coinage, the Romans used crudely cast bars of bronze, known as Aes Rude and Aes Signatum as mediums of exchange, in addition to barter. The first coins were crudely struck bronze coins known as aes grave. Between 280 and 211 B.C. the principle coin of the Roman state was the drachm (probably due to the primacy of Greek trade at that time), however, during the Second Punic War, the denarius (tariffed at 10 asses upon its introduction) was introduced. Eventually, the coinage of the Rome settled into the system we are most familiar with, consisting of the following denominations:

Gold Aureus = 25 Denarii

Gold Quinareus = 12.5 Denarii

Silver Denarius = 16 Asses

Silver Quinarius = 8 Asses

Brass Sestertius = 4 Asses

Brass Dupondius = 2 Asses

Copper As (pronounced 'ass') or Assarius = 4 Copper Quadrantes

Brass Semis = 2 Copper Quadrantes

Copper Quadrans

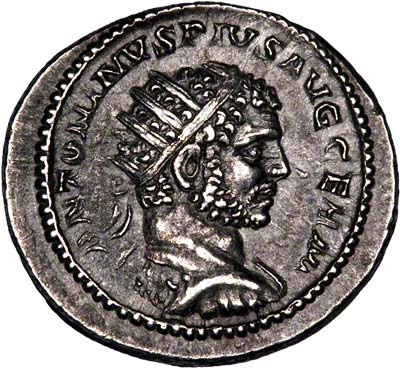

In addition, the Antoninianus* was introduced by Caracalla in 215 and was the most popular circulating coin of the Roman Empire for most of the rest of the 3rd Century. It is believed that the Antoninanus was a double denarius, despite having only 1.5 times the silver weight of an equivilent denarius. Even before fall of the Republic and the establishment of the principate, Roman moneyers were not above issuing low weight coins known as 'fourees'. These were official issue precious metal coins with base metal cores (usually copper). The issuing authorities were certainly not above cheating their own subjects, even though a private counterfeiter would have been subject to the most severe punishments if caught because it was considered to be a form of treasion to undermine confidence in the nation's currency! Even 'honest' issues declined in weight and size over the years however. The denarius, for example, which weighed 4.5 grams at its introduction, ended its days as a bronze coin which weighed slightly less than 2.5 grams, after which the denomination discontinued under Aurelian in the early 270s.

The basics of this original currency system remained in place until the late 3rd century A.D. By this point, the debasement and hyperinflation during the Crisis of the 3rd Century had more or less destroyed the integrity of the Roman currency, neccesitating a complete overhaul of the monetary system under Diocletian (284-305 AD), during which a series of new denominations were introduced, including the bronze Follis, the gold Solidus and the silver Argentus-Siliqua, as well as a series of smaller bronze denominations about which little is known, despite their prolific issue.** This new currency system was made standard throughout the entire Roman Empire, including the 'Greek' provinces (roughly speaking, those parts of the Roman Empire that had once formed part of Alexander the Great's territories), which had previously used a currency based around the old Tetradrachm, which had been similarly debased from silver to billon (an alloy of less than 50% silver) under Roman rule.

The currency of the Roman Empire came to an end around the late 5th - early 6th Century A.D.***

Roman Mints

Much of Rome's coinage was struck, not unnaturally, in Rome itself. However, branch mints had been established even during the days of the Republic. This was especially the case during the period of instability and civil wars preceding the Imperial period, when the loss of control of the Roman mint by one faction or the other meant that they had to establish provincial mints in territory which they did control to pay their expenses.

During the golden age of the Roman Empire (late first to late second century) Rome acquired a virtual monopoly on the production of coins, however, as political instability made a return to the Roman Empire during the third century, it became expedient to open more provincial mints in order to minimise the dangers of transporting shiploads of coins through unstable areas to far flung provinces of the Empire. Under Valerian (253 - 260), coin production became much more decentralised (not to mention more debased), with the mints of Lugundum resuming production after 170 years of inactivity, in addition to Antioch, Milan and Viminacium.

The collapse of central Roman authority under Valerian's son Gallienus (253 - 268) led to the creation of several new mints, both in the rebellious rival Empires of Palmyrene and Gaul, and in the central remains of the Roman Empire still controlled by Gallienus, including at Siscia and Cyzicus.

The expansion of mints continued even after the recovery of the rebellious provinces, when Aurelian (270 - 275) opened more mints in Siscia, Serdica, Tripolis and Ticinum, among others. In addition to the hyperinflationary policies which were accelerating the production of coinage to levels which even the massive mint at Rome could no longer cope with alone, a large-scale revolt at the Roman mint, which Aurelian only put down with considerable difficulty, led to the Roman mint being temporarily closed and production shifted elsewhere to make up the shortfall. Although the Roman mint was later reopened, it never again regained the overwhelming importance it had once had.

In 287, the Roman commander of the Classis Britannica revolted and seized control of Britain, establishing new mints in London, and a mysterious 'C' mint, thought to be either Colchester or Clausentum (a now vanished Roman town near modern day Southampton). When Britain was restored to the Empire following Allectus' defeat in 296, the 'C' mint was closed down, but the London Mint remained open until 325. As the Roman Empire came under pressure and began to lose territory in the 5th century, Mints in the west were closed down and some of them transfered to the East. The Roman mint struck its last issues in 476 A.D. shortly before the final collapse of the West.

Roman Mintmarks

The following is a list of all the major known mints in the Roman Empire, including their mintmarks and presumed length of operation:

Alexandria: (ALE, SMAL) 294-474

Ambianum: (AMB) 350-353

Antioch: (AN, ANT, ANTOB, SMAN) closed sometime before 474.

Aquileia: AQ, AQVIL, AQOB, AQPS, SMAQ (294-c.425)

Arelate (also sometimes known as Constantina): A, AR, ARL, CON, CONST, KON, KONSTAN (313-c.475)

Barcino: SMBA (409-411)

Camulodunum (Colchester) or Clausentum: C, CL (287-296)

Carthago: K, PK, KART (296-307, 308-311)

Constantinoplis: C, CP, CON, CONS, CONSP, CONOB (326-Byzantine times)

Cyzicus: (CVZ, CVIC, CVZICEN, SMK) Closed sometime before 474.

Heraclea: H, HT, HERAC, HERACL, SMH (291-c.474)

Londinium: L, ML, MLL, MLN, MSL, PLN, PLON, AVG, AVGOB, AVGPS (287-325)

Lugdunum: LG, LVG, LVG, LVGD, LVGD, LVGPS, PLG (closed in 426)

Mediolanum: MD, MDOB, MDPS, MED (364-475)

Nicomedia: MN, NIC, NICO, NIK, SMN (294-c.474)

Ostia: MOST (308-313)

Ravenna: RV, RVPS (c. early 5th century-475)

Roma: R, RM, ROMA, ROMOB, SMR, VRB, ROM (closed 476)

Serdica: SMSD, SER (303-308 and 313-14)

Sirminium: SM, SIRM, STROB (320-326)

Siscia: SIS, SIC, SISCPS (closed 387)

Thessalonica: COM, COMOB, SMTS, TS, TES, TESOB, THS, THES, THSOB (298-c.474)

Tisinum: T (closed in 326)

Treveri: SMTR, TR, TRE, TROB, TRPS (291-c.430)

Please note that some cities share the same lettered mintmarks (e.g. 'C' for Constantinoplis as well as for Camulodunum/Clausentum), therefore other factors need to be taken into consideration when identifying the mintmark. Fortunately in the case of the above example, the Constantipolis mint and the Camulodunum/Clausentum mints were not operating at the same time as each other, so dating the coin will assist in identifying the mint.

Also beware of confusing Officina marks for mintmarks. At many of the mints, the individual workshops were identified by letter. Usually, the officina mark is located in the reverse field, but is sometimes present in the exergue at the bottom, were one would normally expect to find the mintmark.

Themes on Roman Coinage

In the Roman Republican period, Roman coins typically depicted a profile bust of a patron god or goddess on the obverse and a commemorative illustration on the reverse, usually with the name of the moneyer underneath. For most of this period, portraits of living people were not depicted on the coins, as this was considered to be hubristic and even monarchical. This changed in the early 40s B.C. when Julius Caesar had his portrait placed on coins. The indignation this caused amongst his contemporaries was one of the reasons, albeit a relatively minor one, that contributed towards the republican plot that led to his eventual assasination in 44 B.C.***

However, following the fall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Principate under Augustus, the tradition of not depicting living persons on Roman coins was permanently abandoned, and almost every coin minted by the Romans from that point carried a portrait of the Emperor(s) or a member of his family on the Obverse. The Reverses were typically used for propaganda purposes, depicting deities, themes and events which the Emperor wished to be associated with, such as military conquest, prosperity, improvements to public health etc.

Precious metal issues were issued in the name of the Emperor alone, but the base metal issues were (nominally at least) issued by the Senate (represented by the letters 'S.C.' on the reverse, standing for 'Senatus Consulto'). During the hyperinflationary crisis of the 3rd Century A.D. the distinction between base and precious metal issues became blurred and the letters 'S.C.' disappeared from the coins as the Empire moved over from the 'Principate' model to the 'Dominate' one, in which all pretence of constitutional government was abandoned in favour of dejure as well as defacto absolute monarchy.

Following the accession of Constantine the Great in 306, pagan themes gradually dissappered and were replaced with overtly Christian themes, such as the 'Chi-Ro' or 'PX' depicted on a legionary banner. The pagan themes were briefly revived under Julian the Apostate, but abandoned permanently after his death. As the Roman Empire gave way to the Byzantine era, profile portraits came to be replaced by facing busts and the latin legends would eventually give way to greek ones.

*The term 'Antoninianus' (named for Antoninus, Caracalla's Cognomen) is an invention of later historians and numismatists. The contemporary name for this denomination is unclear.

**Sadly, the 'Dark Ages' as they had later become known, left later historians bereft of written source material for much of the late imperial period. This was due to a combination of a decline in literacy, the destruction of many written records in the midst of ravaging Visigoths, and perhaps a lack of interest amongst contemporary recorders in writing about something as mundane as the lower denominations of the new Roman currency system (which would have presumably been completely irrelevent to the average literate scribe, who would have a much higher income than an unskilled labourer, who would themselves have considered these small bronze issues of fairly negligable value).

***The date at which the Eastern Roman Empire gave way to the Byzantine Empire is controversial. As far as most numismatists are concerned, the date marking the end of Roman coinage and the begining of Byzantine coinage would fall around the time of Anastasius I (491 - 518) who instituted a major currency reform during his reign which turned the late Roman currency system into a more recognisably Byzantine one.

Catalogue of Roman coins for sale.

Order Form - UK

Order Form - USA

Order Form - EU

Order Form - Rest of World

Buying Coins

We also buy coins, please see our We Buy Coins page.

If you want to find the value of a coin you own, please take a look at our page I've Found An Old Coin, What's It Worth?

| ...at the Lowest Possible Price |

|

32 - 36 Harrowside, Blackpool, Lancashire, FY4 1RJ, England.

Telephone (44) - (0) 1253 - 343081 ; Fax 408058; E-mail: enquiries@24carat.co.uk The URL for our main page is: https://24carat.co.uk Web Design by Snoop |