| The Very Highest Quality Information... |

| Greek Coins |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Nation of City States

The history of Greek civilisation is the oldest in Europe. Written records dating back to the 18th Century BC have been uncovered in Crete that were left behind by the Ancient Minoan Greeks. The Classical Greeks are thought to be descended from 1 of 4 different tribes; The Dorians, Aeolians, Ionians and Achaeans. Each of these tribes spoke their own Greek dialect, except for the Achaeans, who spoke their own version of Dorian Greek.

By the beginning of the 1st Millennium BC, the major cities that Greece was famous for had begun to emerge, such as Athens and Sparta. Other Greek cities, such as Megara, Corinth, Thebes and other emerged later.

Athens, the future capital of Greece, was perhaps the greatest of these, although it was humbled on more than one occasion by its rivals, often led by redoubtable Spartans, Athens' bitterest enemy.

As many of these great Greek City states grew, they went on to found colonies elsewhere on the Greek mainland, as well as in the Balkans, Black Sea Coast, Southern Italy and Sicily.

Many of the Greek city states in Ionia (modern day Turkey) fell in the early 5th Century to the expanding Achaemenid Persian Empire, but were held in check in Mainland Greece by an alliance of city states and finally pushed back.

Alexander the Great

The 4th Century saw the rise of the Kingdom of Macedon as the greatest of the Greek states. Under Philip II, Macedon fought a series of campaigns that brought most of the Greek city states into submission, with the notable exception of Sparta, which he left well alone. Philip II had been planning to conquer the Persian Empire at the time of his assassination in 336 BC.

Instead, it fell to Philip II's son, Alexander III to lead the armies of Greece to victory against the Persians. Alexander III's leadership and military prowess were legendary, and by the time of his death at the age of only 32 in 323 BC, Alexander the Great had not only conquered the Persian Empire, but had carved out an even larger Empire of his own that not only covered Greece and Anatolia, but stretched as far south as Egypt (where he founded the city of Alexandria) and as far east as the River Indus. Although this Empire quickly collapsed following his death, the Empire was divided between his generals, who carried on ruling their respective Empires as Hellenic states, essentially spreading Greek culture throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East.

Roman Greece

Following the collapse of Alexander's Empire, the Greek City states re-emerged. They largely divided themselves into two leagues, the Achaean League (including Thebes, Corinth and Argos) and the Aetolian League (including Athens and Sparta). These leagues were almost constantly at war with each other and their respective allies until Greece was finally conquered by the Romans in 146 BC.

The Romans greatly admired Greek culture however, and most educated Romans could already speak Greek. By 30 BC, most of the Greek World had been conquered by the Romans. The Roman admiration for Greek Culture meant that they largely protected it under their rule, in contrast to the fates of many other subjugated peoples had found themselves Latinised and their native cultures suppressed by their chauvinistic Roman overlords. Late in the Roman era, Greece, along with most of the Roman Empire, rapidly began to convert to Christianity following the conversion of Emperor Constantine the Great in the early 4th Century.

Byzantium

As the Roman Empire in the West Collapsed (including Rome itself) the centre of Roman Power shifted east to Constantinople (which had been built by Constantine on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium). For centuries after the demise of Imperial Rome, the Byzantines referred to themselves as 'Romans', but to Western Europeans, they were known as 'the Greeks' because culturally, that is what they were.

The Christianity of the Byzantine Greeks diverged from the Latinised west following the Great Schism in 1054. From this point on, Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy emerged as separate branches of Christianity.

The Byzantine Empire was gradually eroded by the Ottoman Turks however, and in 1453, Constantinople fell. By this point, most of Greece had already been in Turkish hands for many years.

Greece under Ottoman Rule

The Greeks remained under Ottoman rule for the better part of 400 years. They clung bitterly to their Orthodox Christian faith in spite of many pressures and incitements to convert to Sunni Islam. They were forced however, to pay the Jizya tax to the Sultan, and if Greek Christian families had five or more boys they were forced to hand one of them to train as a member of the Janissary Corps, the Sultan's elite household troops. Greece became an economically backward and increasingly ruralised province under its Turkish Overlord.

Independence

Uprisings against Turkish rule were periodic, but usually crushed within a short space of time. However, in 1821, a general uprising began, lasting until 1832 which saw the emergence of the Kingdom of Greece. During the course of this conflict, many atrocities were committed on both sides, and many Turks living in Greece were forced to flee during the uprising and its aftermath.

The Greeks chose a Bavarian prince, Otto of Bavaria as their King, and he ruled as an absolute monarch until a constitution was established in 1843.

Kingdom of Greece

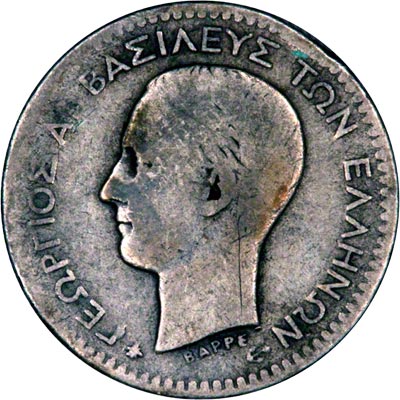

Otto died without issue in 1863, and the Danish Prince George was elected by the Greeks to become their new king. Throughout the 19th and early 20th Centuries, the Greeks longed to recapture Constantinople and liberate the majority Greek areas of Turkey. They were prevented from entering the Crimean War against the Ottomans by the British and the French, as they were again during the Russo-Turkish war of 1877. The aftermath of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution in Turkey saw all of the Balkans liberated from Ottoman control, except for Constantinople and its surroundings.

In 1913, George I was assassinated and his son Constantine came to the throne. Greece, led by Prime Minister Venizelos controversially entered the First World War on the allied side, against the wishes of the Germanophile King Constantine, who was forced out in 1917 in favour of his son Alexander. The division of Greek politics into pro-neutral and pro-allied factions was profound and often violent, leading to a national schism that lasted many years after the war.

However, the allied victory saw Greece gain the whole of Thrace, as well most of the western coastline of Anatolia; however, most of these gains were lost again during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922. The following year, the Greek and Turkish Governments agreed on a population exchange whereby Greeks in Anatolia would by expelled and settled on mainland Greece whilst in Greece all Muslims (lumped together as 'Turks') would for their part expelled and forced to settle in Anatolia.

George II and World War II

Constantine I, who had returned in 1920 following the death of Alexander, was forced to abdicate once again in 1922, and was replaced by his son, George II. However, in the wake of the loss of the Greco-Turkish war and a failed Royalist coup to take back Royal Power, George II was 'asked' to leave in 1923. A republic was declared the following year.

Greece then entered a period of political instability and suffered from no less than 23 changes of Government between 1924 and 1935, including a dictatorship and 13 coups. Following the last of these coups, led by General Georgios Kondylis in October 1935, a plebiscite was held, in which almost 98% of the population voted to restore the monarchy and (they hoped) political stability to their benighted country.

Greece tried to remain neutral during World War II, however, they found themselves the victim of the Italian dictator Mussolini's imperial pretentions, and found themselves at war with him in October 1940 after rejecting his ultimatum to allow him to station Italian troops in Greece. The Italians invaded Greece via Albania, but the Greeks, who were not particularly renowned for their military strength at this point, ended up pushing the Italians back into Albania and threatened to drive them back into the Adriatic. As British troops began to be deployed in Greece to aid them against the Italians, Hitler was forced to come to the aid of his hapless Italian ally, and German troops invaded and occupied Greece via Yugoslavia in April 1941.

Greek Civil War

During the Second World War, Greek Partisans fought against the Germans, but were divided broadly into pro-Royalists and pro-Communists. The end of World War II and the end of German Occupation saw a civil war break out between the pro-Royalists and the Communists. Thanks to British support (and a Soviet Agreement not to intervene on the Communist side) the forces of the Royal Government emerged victorious in 1949. However, the Civil War had bitterly divided Greece and done much to damage an already ravaged economy.

Junta

An election was held in 1967, the results of which seemed likely to see a government partly composed of United Democratic Left Party members. Many rabid anti-communists viewed this likelihood as the precursor to domination by the Soviet Union, and so a group of Army officers, led by Brigadier Stylianos Pattakos and Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos, launched a coup to seize control of the government. What followed was a series of right-wing military governments, known collectively as 'the Junta'. Constantine II attempted a countercoup to take power back from the Junta, but when this failed, he went into exile in Italy. The Junta attempted to legitimise their government, but Constantine II insisted on the restoration of democracy and the constitution as a prerequisite. In 1973, the Junta lost patience and declared the King a traitor and a collaborator and Greece as a republic.

The Junta collapsed after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. However, whilst this led to the restoration of democracy, a referendum was held which voted to keep Greece a Republic.

Greece Today

In 1981, Greece joined the EEC (later the EU). Greco-Turkish relations continued to be strained until 1999, when earthquakes hit both countries. The first hit Turkey, prompting a huge relief effort from the Greek government and ordinary Greeks. This was reciprocated by Turkey a few months later when an earthquake hit Athens. However, at the time of writing, Greece is undergoing a debt crisis exacerbated by its membership of the common European currency, the Euro.

Coinage of Greece

The Greeks did not invent coinage; however, they were amongst its earliest adopters after it was invented by the neighbouring Lydians in the 7th Century BC. Soon after, Greek City states began to issue coins of their own, featuring designs representing their origin. The coins of Athens typically featured an Owl, of Aegina a Tortoise. Some designs and mintmarks were related to a pun. Rhodes for example, featured a rose (which is called a 'rhodon' in Greek). The standard unit of currency in the Greek world was the drachm (meaning 'graspful').

Eventually, coins of the Athenian Attic standard of 4.3 grams of silver per drachm became the general standard throughout the Greek World. This was aided by the plentiful supplies of silver Athens had access to at Laurium, as well as the dominance of Athens as a trading and maritime power.

Silver tetra drachms (4 drachma) became the standard trade coin used in Greece, supplemented by smaller silver drachm and stater or didrachm (two drachm) pieces, and by bronze obols (6 of which made a drachm). Gold coins were also issued, but these issues were comparatively rare, and their value fluctuated against their silver counterparts, and a defacto silver standard was used throughout most of the ancient world, including Greece.

When Greece and the Hellenic World came under Roman control between the 2nd and 1st Centuries BC, the Romans allowed the Greeks to maintain their own currency system based around the world, until the Helleno-Roman Emperor Diocles (Diocletian) imposed a uniform standard of currency throughout the Empire.

Throughout most of the Byzantine period, Byzantine issues, which evolved from the currency system of the late Roman Empire were struck for use in Greece. During the Ottoman period, Ottoman currency was used in Greece, as it was elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire.

Greek independence saw the re-emergence of the drachm. This first modern drachma was subdivided into 100 lepta, and copper coins of 1, 2, 5 and 10 lepta were issued, along with silver quarter, half, 1 and 5 drachma. This issue was originally introduced based on the old Attic standard, and each 4.5g coin contained 4.2g of silver within a 0.900 fine silver alloy. A gold 20 drachma coin was also issued.

In 1868, Greece joined the Latin Monetary Union, and the drachma was made equivalent to the French franc. Based on a gold standard, silver coins were now considered supplementary to standard gold 20 drachmae issues containing 0.1867 grams of gold. New coins were issued following the adoption of LMU and the Gold standard. The new 5 and 10 lepta coins were referred to as obols and diobols, after the ancient names for bronze coins in classical Greece.

The Latin Monetary Union collapsed as a result of World War I, and in 1926, a new series of coins was introduced, with the lowest denominations of 20, 50 lepta, 1 and 2 drachmae being issued in cupro-nickel. Pure nickel 5 drachmae coins were also issued, as were silver 10 and 20 drachmae.

Invasion and occupation by Nazi Germany had led to skyrocketing inflation, and in 1944, a new drachma was introduced, replacing the old drachma at 50,000,000,000 to 1. No coins were issued for this second drachma, which was issued in banknote form only.

In 1953, after another bout of inflation, Greece introduced the third drachma, exchanged at 1000 to 1 and pegged to the US dollar at 30 drachma to the Dollar. The Drachma was decoupled from the Dollar in 1973 following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and by the time it was replaced by the Euro in 2002 it took 400 drachma to equal 1 US dollar.

Until 1973, coins of the third drachma included aluminium holed 5, 10 and 20 lepta, along with cupronickel 50 lepta, 1, 2, 5 and 10 drachma. A silver 20 drachma piece was introduced in 1960.

Following a series of devaluations, the coins of the Greek drachma changed size, denomination and composition to reflect the collapse in the drachma's value. By the time the drachma was replaced by the Euro in 2002, coin denominations consisted of 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 drachmae. However, by this point, the 10 drachma was the lowest denomination still generally used in circulation.

Today, for better or worse (probably worse) Greece uses the Euro. Notably, the Greek Euro coin features the Owl of Attica on its obverse, a reference to the design of the once ubiquitous Athenian Tetra drachm that once dominated trade between the Greek states From Italy to the Black Sea.

For Sale and Wanted

If you are interested in coins from Greece please see our product index:-

Greek Coins

| ...at the Lowest Possible Price |

|

32 - 36 Harrowside, Blackpool, Lancashire, FY4 1RJ, England.

Telephone (44) - (0) 1253 - 343081 ; Fax 408058; E-mail: info@chards.co.uk The URL for our main page is: https://24carat.co.uk |

Web Design by Snoop |